By Andrew Heald Natural Resources Consultant.

There is an old joke that if you want 3 opinions ask 2 foresters; well if you ask the same foresters to define “sustainable forest management” then you will probably get a lot more than 3 opinions and the usual response is “Well, it’s complicated; and it depends.”

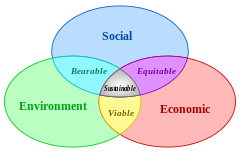

However most definitions of sustainability tend to include:

- Living within the limits of what the environment can provide

- Understanding the many interconnections between economy, society and the environment

- The equal distribution of resources and opportunities.

Its better demonstrated in this graphic:

So what does this mean in terms of sustainable farm woodland – “Well, its complicated; and it depends.”

Farming and Forestry in the UK

Farm woodlands have a lot of different uses, they may have been planted for wind breaks, to supply firewood and timber, or simply for aesthetic reasons, quite simply if they are sustainable then they will be providing that firewood or sheltering those pheasants, in 50 years’ time just as they are now.

The other aspect of sustainability and forests is the issue of time and scale. In simple terms completely clearfelling a 1 ha small woodland may be un-sustainable, but clear felling 1 ha coupe, which is part of 40 hectare forest could be completely sustainable.

Traditionally in the UK there has been a division of opinion that all broadleaves are good and all exotic conifers are bad – Scots Pine being the exception. Much of this opinion was driven by the afforestation practices of the 1960’s and 70’s when the UK Government was keen to establish a UK forest and sawmilling industry. The legacy of this planting is all around us in Scotland, but with a change in understanding and more sensitive management, these plantations are being felled and replanted and will deliver a wider range of benefits with a greater range of species.

Forestry in the UK is very heavily regulated, much more so than agriculture; Scottish Government represented by the Forestry Commission is both the largest forester in Scotland and also the industry regulator. All clear felling and replanting, must be undertaken with their approval, and a range of grant aid is also available.

The breadth and depth of regulation is significant and can be quite daunting the first time it is encountered, many farmers might chose to use a consultant or Chartered Forester (see further information) to help them navigate through both the regulation and the grant aid.

Farming and forestry in the UK have often not co-existed happily, traditionally forests were cleared to create agricultural land, and that later afforestation created a net loss of grazing land and threatened rural (ie farming) livelihoods. The loss of Schedule D Tax Relief in 1984 and increasing land prices, brought the afforestation of the 1970s to an abrupt halt and planting of forests has only recently begun to increase.

Multi-purpose forestry

Woodlands can deliver a wide range of benefits to the woodland owner and to the wider community. The obvious immediate benefits can include shelter, timber or firewood, but at the same time woodlands can be storing CO2, providing important wildlife habitat and recreation.

Some of the original large scale plantations schemes attracted criticisms precisely because they were single-purpose to grow a “strategic reserve of timber” as required by the UK Government. As these plantations have been reimagined and redesigned to deliver more benefits (particularly recreation and biodiversity) and with a greater range of species, then they have become more widely appreciated, which in turn lead to the outcry at the proposed FC sell off in 2011.

Climate Change

The role of trees and forests in climate change can be complicated when trying to explain how using trees for timber can be part of sustainable forestry. Trees convert sunlight and CO2 into wood, the paper you are reading this on, or the desk you are working at is stored CO2. So well managed forests can be sustainably harvested and can continuously store CO2 both in the trees and the soil and also the products made from that timber. An old piece of furniture or the beams in old barn, could actually be stored carbon dioxide from the 18th or 19th century. The more things we make out of wood, then the more CO2 is stored and locked up, the important issue is that the forests are managed sustainably and replanted.

Sustainably managed woodlands also store and sequester CO2 in the soil, both in terms of roots but also soil carbon in organic matter, which is partly accumulated material from tree leaves or needles; current research suggests that there can be more Carbon stored below ground than above.

The Scottish government has set a target of 60,000 ha of new planting by 2020, and that 60% of that should be commercial productive woodland; this is an ambitious target and which we will struggle to meet.

Flooding

The recent flooding events, have led to much discussion around the roles of trees in upland catchments and whether they can or can’t have an impact downstream. The answer again is, well its complicated but long term research at Pontbren in mid-Wales has demonstrated that well planned shelter belts and hedges can improve the infiltration of water my upto 60 times compared to grass only hillsides. Better infiltration means that rainwater will run-off the hill more slowly, reducing flood peaks downstream and also reducing erosion and so the amount of silt in the river system.

You can read more about the farmer lead research here – http://www.pontbrenfarmers.co.uk

Interestingly research undertaken by the Woodland Trust and Harper Adams University College, in 2012 found that well planned shelter belts on arable farms could also play a significant role in mitigating against drought by reducing wind speed and so evapotranspiration in crops.

Trees on farms can also shelter buildings and reduce the risk of spray drift on arable feeds; but there can be a host of other benefits. Research on the Tweed river catchment has encouraged landowners to fence out stream and river banks, and to plant trees which have helped cool the water temperature, which in turn has led to an improvement in the fishing.

Forest Certification Globally

Any discussion on sustainable forest management, has to include “forest certification”, and the potential alphabet soup of FSC, PEFC and SFI. Global concern around the sustainable management of forests in the 1980’s lead to the development of formal forest certification whose roots were established in the UK; disappointed with government inaction, environmental organisations such as World Wide Fund for Nature, turned to industry for a different approach to tackle the problem. In the UK, WWF established the 1995 Group which included major timber retailers such as B&Q, and other organisations which had been involved with direct action, to create an NGO-Business partnership. After 18 months of consultations in 10 different countries the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) was finally established in 1993.

FSC’s mission is to “promote environmentally appropriate, socially beneficial and economically viable management of the world’s forests”. Initially the concern and FSC was aimed at protecting tropical forests, but this quickly spread to the boreal forests of Canada and Scandinavia, and onwards to include forestry plantations in the UK.

Use of the FSC logo is intended to signify that the product comes from a responsible source, i.e. a well-managed forest. The logo is meant to give customer the choice of buying products, which support responsible forests, with an independent, global and credible label for forests products. Rival schemes such as PEFC, developed in parallel and are more common in some of the forest dominated Scandinavian countries and are perceived as more industry friendly.

UK Woodland Assurance Scheme (UKWAS)

There was much debate on how best to demonstrate sustainable forest management in the UK context. Initially there was considerable disagreement; some advocated reliance on the governmental controls already in place and others championed a new process involving independent verification against a published standard defining sustainable forest management.

In time, the UK’s forestry, environmental and social communities chose to work together to develop an independent standard to reflect the requirements of the UK Government’s UK Forestry Standard and through this the guidelines adopted by European Forestry Ministers at Helsinki in 1993 and Lisbon in 1998.

The launch of the UK Woodland Assurance Standard (UKWAS) in 1999 was a landmark event for UK forestry; it was achieved through a sense of common purpose and the sheer hard work of those involved and it put the UK at the forefront of the global forest certification movement. The standard was adopted by the Forest Stewardship Council and later by PEFC UK as the basis for their UK certification programmes. This dual recognition approach is unique in global forestry.

The main forest certification schemes have broadly similar principles and criteria, against which management is audited:

- Biodiversity of forest ecosystems is maintained or enhanced

- The range of ecosystem services that forests provide is sustained:

– they provide food, fibre, biomass and wood

– they are a key part of the water cycle,

act as sinks capturing and storing carbon,

and prevent soil erosion

– they provide habitats and shelter for people and wildlife

– they offer spiritual and recreational benefits - Chemicals are substituted by natural alternatives or their use is minimized

- Workers’ rights and welfare are protected

- Local employment is encouraged

- Local community rights are respected

- Operations are undertaken within the legal framework and following best practices

Concluding remarksThis article started by saying that sustainable forest management could be complicated, but this is mainly because woodlands and forests provide a lot of different benefits and services, and it is balancing those benefits and services, particularly in a small woodland area that can be complicated. The easy solution to this conundrum is to plant more trees, and then you will have more shelter belts, more firewood, more stored carbon dioxide and more choice as to which trees you fell, retain or thin out.

Trees and woodland on a farm can provide so much with relatively little input and demonstrate an optimism and investment in the future. The landscape and trees around us, are the result of previous land managers, thinking and planning ahead; we now know that our climate will become more unpredictable in the future and with more storms. It is important that we start to mitigate against this unpredictability and to make our landscapes more resilient and robust, a very simple way to do this is to plant more trees, the right trees and in the right places.

“The true meaning of life is to plant trees, under whose shade you do not expect to sit.”

(Nelson Henderson who played rugby for Scotland 1892 )

Andrew is a Natural Resources Consultant with vast international experience.

Further information

Trees and arable farms http://www.woodlandtrust.org.uk/mediafile/100083900/Managing-the-Drought…

Ponbren – upland trees and water infiltration – www.pontbrenfarmers.co.uk

Confederation of Forest Industries – http://www.confor.org.u

Forestry Commission Scotland – http://www.forestry.gov.uk/scotlan

Forest Certification – UK Woodland Assurance Scheme – http://ukwas.org.

For professional advice and a list of Chartered Foresters – http://www.charteredforesters.org/